In this online teach-in, anthropologist Darren Byler helped us unpack the interconnected state terror between China and Israel. It compared the parallel colonial tactics between Israel and China, uncovering their collaboration in advancing each other’s “war on terror” against peoples they each label as “potential terrorists”: Palestinians and Uyghurs. In both cases, “anti-terriorism” narratives are used to demonize indigenous people and ethno-racial minorities, and “safe city” (or “smart city”) campaigns and dataveillance technologies serve as a guise for expanding colonial control and upholding settler supremacy in the occupied territories.

About the speaker

Dr. Darren Byler is an anthropologist of state power, policing and incarceration, and infrastructure of surveillance in Global China. He is Assistant Professor of International Studies at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, Canada. Through his two-year fieldwork, Byler has built bonds with Uyghur and other Turkic Muslim communities in Northwestern China and has written extensively about the ongoing oppression of Muslim minorities in China. He is the author of 𝙏𝙚𝙧𝙧𝙤𝙧 𝘾𝙖𝙥𝙞𝙩𝙖𝙡𝙞𝙨𝙢: 𝙐𝙮𝙜𝙝𝙪𝙧 𝘿𝙞𝙨𝙥𝙤𝙨𝙨𝙚𝙨𝙨𝙞𝙤𝙣 𝙖𝙣𝙙 𝙈𝙖𝙨𝙘𝙪𝙡𝙞𝙣𝙞𝙩𝙮 𝙞𝙣 𝙖 𝘾𝙝𝙞𝙣𝙚𝙨𝙚 𝘾𝙞𝙩𝙮 (Duke University Press, 2021) and 𝙄𝙣 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝘾𝙖𝙢𝙥𝙨: 𝘾𝙝𝙞𝙣𝙖'𝙨 𝙃𝙞𝙜𝙝-𝙏𝙚𝙘𝙝 𝙋𝙚𝙣𝙖𝙡 𝘾𝙤𝙡𝙤𝙣𝙮 (Columbia University Global Reports, 2021). He is also a co-translator of 𝙏𝙝𝙚 𝘽𝙖𝙘𝙠𝙨𝙩𝙧𝙚𝙚𝙩𝙨 (Columbia University Press 2021), a novel by Uyghur writer Perhat Tursun who has been disappeared and imprisoned by the Chinese state until today.

Teach-in

Context

This teach-in was held on the 166th day of genocide and the 76th year of Zionist occupation of the Palestinian homeland. Palestinians are still fighting for the freedom that the world owes to them. Al Shifa Hospital in North Gaza was attacked again, where journalists and medical staff were abducted and civilians were killed. Flour massacres have continued to happen for more than 7 times. Israel's settlers are murdering Palestinians every minute, and there are people who sacrifice their careers or even life to speak up and withdraw from being complicit in the acts of genocide.

We are having this teach-in not for pure intellectual satisfaction, but as an urgent call for action.

Palestine Solidarity Action Network is a group of Sinophone activists and students. Individually we work in different spaces of Palestine solidarity organizing: in the city, on campus, at workplace, via publication, and so on. Collectively we work on educating on BDS (Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions) and acting on ties of complicities that maintain apartheid Israel, including those with and from China, the home country of many of us.

As we educate ourselves in Palestinian struggles, we feel a strong imperative to decolonize ourselves more deeply and connect the struggles in Palestine and those at home. We consider this an urgently necessary discussion. As Chinese activists in diaspora, we've seen radio silence, if not straight-out support for Zionism, in the past few months, from the Chinese overseas dissident community, who have nonetheless been advocating for human rights defenders who experience state violence in China as well as on on ethnic cleansing of Uyghur and Turkic muslims. In the case of Palestine, they put themselves to Zionist interest by spreading misinformation and demonizing Palestinian resistance.

At the same time, within the Palestine solidarity organizing scene, especially in the United States, we've seen statements that dismisses the violence of internal colonialism of states that expressed a pro-Palestine position. We've also seen the Chinese state propaganda tap into the Gaza genocide committed by the US to cover up its own crimes and deny the cultural genocide and mass incarceration in Uyghur homeland. We hope that this teaching could bridge some gaps.

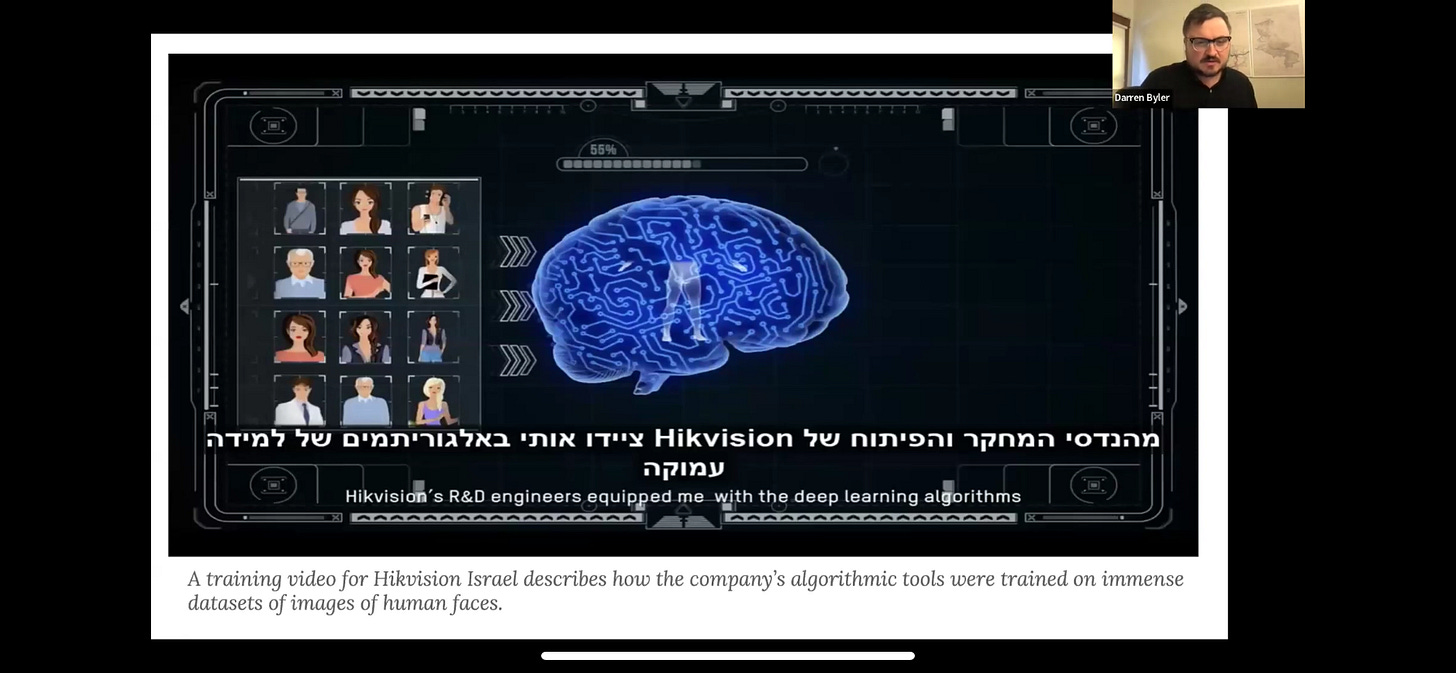

We also hope that there will be more activists putting attention to Hikvision, the policing regimes it facilitates, and the complicity of technology in general.

Presentation

The talk I'm going to give is for thinking about Palestine and its relationship to “Xinjiang” - the new frontier, or what some people refer to as East Turkestan, and for understanding how settler colonialism and the surveillance state are interconnected in both of these places.

I'd like to start by reading just three paragraphs from the Chinese translation of my shorter book In the Camps. It features this man, Pan Yue.

In his 2002 dissertation, Dr. Pan Yue, the current commissioner of China's Ethnic Affairs Commission, proposed that a mass migration of 50 million Han people to Tibet and Xinjiang would simultaneously address three major problems confronting China: overpopulation, the demand for resources, and the problem of ethnic and religious difference. “Problem.” That's how he framed it. Pan, who became the first Han commissioner of Ethnic Policy in the history of the People’s Republic in 2022, suggested that Han migrants should be considered reclaimers of the Uyghur lands.

The “backwardness” of the frontier, he suggested, had become a danger to national security, fostering terrorist and extremist activity in the post-9/11 world. He called on China to learn from a trifecta of contemporary colonizers: the United States, Israel, and Russia, taking elements of each as a model of how contemporary China should colonize Tibetan and Uyghur lands. He suggested that the Western expansion of settler colonialism in the United States and Russia's imperial settlement of Siberia should be combined with the more contemporary example of Israel's controlled deployment of the West Bank’s settlers and infrastructure in the Occupied Territories of Palestine.

Finally, drawing from a model of China's post Maoist legacy of state-managed economy and export-oriented development, Pan proposed that minorities should be proletarianized through assigned industrial labour - so they should be put to work in factories. In his study, it was clear that Pan wanted to combine a land grab with the dissolution of the Maoist system of ethnic minority autonomy within a socialist political and economic system. He was thinking comparatively about the world system of global capitalism, not as an object of critique or something that should be opposed, but as a way of understanding, mimetically - or in a form of mimicry - what China's place in the world should be within it. China should be a capitalist colonizer just like these other states. Part of what this implies, I argue in the in the book, is that Pan's post-ethnic framework called for the abolition of the limited protections of difference that the Mao era had fostered and, as in the US and Russia and Israel, the replacement of civil liberties and autonomous claims for Muslims and Indigenous citizens with markers of imagined evil: the figures of the terrorist and the proto-terrorist, the terrorists waiting in hiding, the non-secular backward other.

This person is now in charge of ethnic policy in China and he's saying all of these things about how China should learn from Israel, should learn from the United States, should adopt anti-Muslim racism as policy. My books came before some of what Pan proposed, or before it was implemented as it has now been implemented. But it speaks to this process of adapting global discourses, global tactics, global technology for new purposes in a Chinese context. It also speaks to the way that that technology begins to travel, and how it moves from China to Israel, how Israel's framing of what it’s doing to Palestinians moves to China. There's a constant dialectic – a back and forth – between these two states as well as other states that are doing similar things.

My work draws on two years of field work in the region over a decade. My last visit to the region was in 2018, which was after many of hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs had already been disappeared, taken to what were called re-education camps by the Uyghurs that I met. Then in 2020 I went to Kazakhstan to interview people that were coming across the border, many of whom had been in the camps themselves.

So I've drawn both Uyghur and Chinese language interviews. I speak both languages to varying degrees. Many of my interviews and people I've learned from are in the Uyghur community, some of whom are my closest friends. I've also become friends with Han people who are opposed to what's happening and are trying to resist it in the certain ways that they can from inside China. [I also interviewed] government contractors, people that build and implement the system.

I also worked with a journal called The Intercept, who were for a couple of years looking at internal police documents that had been obtained by the journal from a company called Landasoft, which advertises itself as China's Palantir (one of the largest policing companies and military intelligence companies in the United States). Landasoft had built the Ürümqi mobile policing system, so within these internal files are very detailed documents describing who's being detained, how they're being detained, how the surveillance system works, the capacities of the system and how the system was built. I also looked at lots of government documents and industry documents to corroborate things that my interviewees told me.

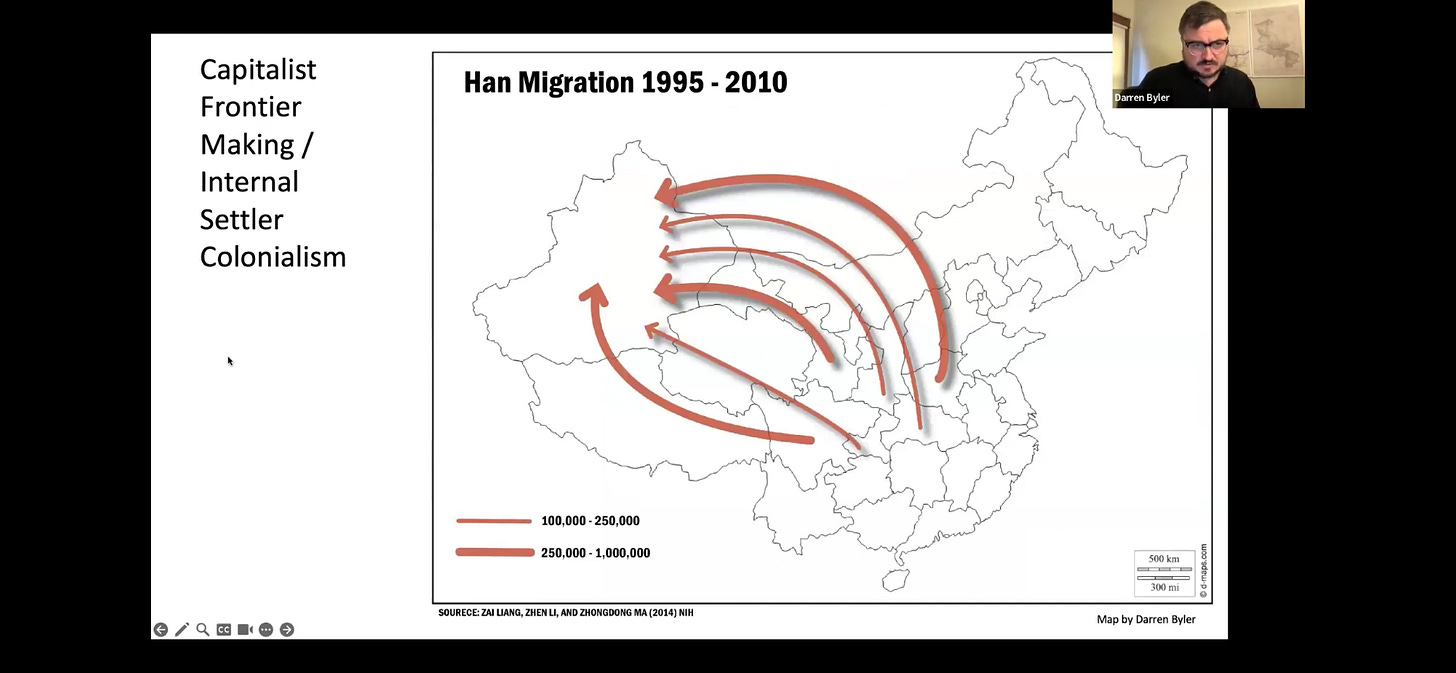

The story of what's happened in Northwest China really started in the 1990s, which was when China was becoming a manufacturer for the world. They needed raw materials to drive their economy, and so we see mass migration of Han people to Northwest China during this period that was incentivized by corporations and by the government.

When those people arrived, they began a process of building out the infrastructure - building the roads and the pipelines, and eventually the service industries that would support the resource extraction economy. This region is a source of more than 20% of China's oil and natural gas, and maybe 40% of China's coal. And then as the infrastructure was built, there was a turn to industrial scale agriculture, particularly in the southern part of the region.

Really what they're doing is turning things that weren't part of the Chinese market into parts of the Chinese market, which is something that Marx would describe as primitive accumulation or original accumulation: they’re building a new frontier of China's capitalist economy, and through that process, also building processes of dispossession, institutional capture or domination, and introducing new forms of occupation.

There has been a Han presence in the north of the region for a much longer period of time, but it was only in the 1990s that large numbers of Han people began to move into the south, which is the Uyghur homeland where the population is more than 90%. That process was really what built the tension between the Uyghur population and the Chinese state and the settlers that were arriving.

It was, first, a kind of material enclosure system – all this new infrastructure – that began to push people out of their homes. Land was rezoned. The same processes had happened elsewhere in China, but in this context it was something done by the Han settlers to the Uyghur population, so it was experienced as a process of dispossession that was undermining the way of life that Uyghurs had.

Over time, other kinds of enclosure, which I'll talk more in a minute, of digital enclosure and assigned labour, also were built. But initially it was just the material enclosure and then the institutional capture, which was the ways in which the banking system, the education system, the grassroots political system, were all captured by this new population of people. And so, Uyghurs, who, in the past during the Maoist period had a representation in the local political system, now saw themselves being pushed to the side. They saw themselves being disempowered. They also saw the cost of living begin to rise because of the new population of people. But at the same time, a kind of apartheid system was being built that excluded Uyghurs from the new economy, from the resource sector.

All of these structural issues began to produce really dramatic antagonisms between the Uyghur population and the Han population, and so there was a rise in violence. Initially that violence was around land dispossession, people protesting that land dispossession and then protesting police brutality that responded to the protest. They were protesting new restrictions on Islamic practice, which began, to a larger degree, after 2001.

October 11, 2001 is an important date for Uyghur cause one month after 9/11. And it was the first time that a Chinese state official had referred to Uyghurs as terrorists. Prior to this, Uyghurs had been referred to sometimes as separatists, counter revolutionaries, or local nationalists, but now they were talked about in the same way that the United States was talking about Al Qaeda and the Taliban, and was talking about the need to invade Afghanistan and Iraq.

So Uyghur protest was reframed as terrorism and extremism. This reframing means rewriting the history of the 1990s when there were already some protests. Those were now rewritten as terrorism in Chinese state documents.

[One example of] naming Uyghurs as terrorists, or a small group of Uyghurs as terrorists, was the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (or Party), which was based in Pakistan. It was a small number of people, maybe 3 - 5 people who mostly had a media presence, but really had no capacity to carry out attacks. The US designated that group a terrorist organization. They also captured a number of Uyghurs who were in Afghanistan, who were given to the US military as an exchange for a bounty. [The US military] took them to Guantanamo Bay. So the US involvement in naming Uyghurs as terrorists helped to solidify the processes that were already happening in China.

Fast forward over a decade, there was continuing violence. There was a mass event in 2009 of street protests regarding the lynching of Uyghur workers in Eastern China, which then turned into an inter-ethno-racial riot with hundreds of people being killed. Then, in 2014 there's an attack at a train station called 3/1 when a group of Uyghurs killed more than 30 Han people who were just regular civilians. This is referred to as China's 9/11, similar to the ways that Israelis are talking about October 6 and 7 as Israel's 9/11. It precipitated what the Xi administration would refer to as the People’s War on Terror, which meant a radical intensification of policing and internment for Uyghurs.

At the same time, as these events are happening on the ground, there are also new discourses circulating in Chinese policing theory and military theory. Already in the 2000s, you see in the Chinese police academy documents how they're learning from Israel, how they're studying the Second Intifada and how Israel has responded to it, and how China can learn from it in its treatment of Uyghurs.

But I think there's an even more important source when it comes to military strategy, which is, European approaches to countering violent extremism, especially in the UK. So, this book, Policing Terrorism: Research Studies into Police Counterterrorism Investigations, by a CVE expert in the UK, David Lowe, is translated into Chinese. And it becomes used as a model for how Chinese police should understand the potential radicalization of Muslim people, that [they] should be watching how people carry out their religious life: whether or not they go to mosques or not, how often they pray. Teachers should be mandated to track their students, Imams should be reporting, there should be informants in every community. This is what they're saying in the UK.

China is adapting that and saying we're going to do the same thing. We'll do it better; we'll do it with Chinese characteristics. And so you see the study called “Studies of Anti-terrorism and the Xinjiang mode [of anti-terrorism],” which is basically CVE on steroids. It's justification for the mass internment of anyone who you have any reason to suspect of being pious and connected to what they call “foreign Islam,” which they say is a virus that's sweeping through the Uyghur population. “Foreign Islam” means that you've studied the Koran outside of a state academy, and it means that you are potentially learning from teachers of Islam who are based outside of China, or are in China but are not given authorized permission to speak.

Another aspect of this was that, all the way up until 2017, which was when the mass internment system really took off, the Chinese authorities were bringing in UK experts on CVE to teach them the best practices: “how do you do this counter terrorism stuff that you're doing in Europe and how can we adapt it to China?”

One of the things they were learning from the CVE discourse is how important signals and intelligence is; how important it is to track everyone's behaviour online. The ways in which big data and data valence tools can be used to determine or diagnose potential criminality. So there's this move to introduce something that could be referred to as a digital enclosure, which is using state security and private industry together to build forms of population management and control. These systems can't just simply be plugged in and put to work. They need, a lot of human labour. To implement the system, they hired around 90,000 new security personnel. They also mandated Civil Affairs Ministry personnel, which is the social services system in China, to act as volunteers to build the base datasets, to go into all the Uyghur villages and track who's there, write down their names, take their pictures, build a network within the policing system. This is something that's happening right now in, in Israel as well. The military there is mapping the Palestinian population to build a digital enclosure system.

The initial goal in the Chinese case was to break the autonomy of the Uyghur internet, because Uyghurs were originally using Uyghur language and initially the censorship system in China couldn't pick up on what people were saying. So they needed to build new tools that would automate the transcription, translation, and assessment of Ugyhur speech on apps like Wechat. They also needed to be able to detect information and images. And eventually they wanted to be able to automatically detect Uyghur and Kazakh faces, mapping the phenotypes of those faces. So they're automating forms of ethno-racialization.

This is really important for tech companies because it gives them access to state data that's very symmetrical. They’re data sets that really can't be replicated by just scraping the internet. You also get access to state capital. Economists like David Young who's at Harvard has shown is that within two years of developing state security projects, start-up companies developed commercial applications that build on those public security contracts. So there's a really direct kind of connection between doing state security in China and becoming commercially lucrative, like building the facial recognition unlock system for smartphones, for instance. If you do have a state contract, it helps you to accelerate that.

The tech companies were also adapting Israeli tactics. One of the most used devices in Xinjiang was this [data assessment] tool built primarily by Meiya Pico, that reverse engineers or replaces Israeli Cellebrite cyber hacking tools. So initially, Chinese security was using Israeli technology. But as Israel started to stop selling things to China as they're getting international pressure, and because China wants to develop its own technology, Meiya Pico and others began to reverse engineer and build their own tools.

These are dataveillance tools that can be plugged into the person's phone and scan through their digital history looking for over 50,000 markers of banned material. So it looks at the person's QQ, Wechat, and Weibo accounts, and many other things that they've installed. Through these scans, over 1.8 million Uyghurs – according to a state document – were found to have an illegal app on their phone. These diagnostic tools also give a reading of green, yellow and red, red being that the person should be detained, something that then gets replicated in the face recognition system.

If people are determined to be untrustworthy, which is the red code, they were often sent to camps like this one, where they were held for long periods of time. These were medium to maximum security prison spaces that were extremely crowded in many cases. And then they were moved.

So this is the camp facility that you see in the picture from China Daily. And then right behind it is this new shoe factory centre, which is meant to be a new hub of shoe manufacturing. The site of manufacturing is very close to the detention centre, and this is something that you see replicated throughout the entire region. There is over 300 of these kinds of facilities. There's a direct correlation between the re-education camp and factory work. And so, hundreds of thousands of people being detained and then put into factories, another 600,000 people were put directly into prison were criminally prosecuted.

Outside of the camp and prison system, a system of checkpoints was built. These were built by a company called China Electronics Technology Corporation (CETC), which is China's electronic technology corporation and the parent company of Hikvision, which is the world's largest manufacturer of surveillance cameras. CTC built these data doors and face scan checkpoints where you scan your ID and have your face match to it. I went through a number of these when I was in the region in 2018.

What I see in the police data from The Intercept is images like this where Uyghurs are being pulled to the side while Han people, whom you see in the line behind this young man continue to walk through what's called a green lane in the checkpoint. The checkpoints are the clearest example of how an apartheid system is built where one group of people based on their ethno-racial and citizenship categories, are pushed through the convenient line, while the others are forced to be further examined and often subjected to detention.

The internal police data shows the capacities of the system, showing that they have a lot of certainty around image matches that they pick up at these checkpoints. They are 99% sure that it's a match. They also show people in the moment of detention. So this person here is getting red code at the checkpoint and will likely be detained immediately after this.

The system is meant to make everyone searchable. So that all citizens in Xinjiang should be able to be seen, particularly the targeted population, which are the Uyghur and Kazakh populations. You can search their name or their ID number and know where they are at any time. There are also automated tracking systems, so you can see deviation in behaviour if someone is under neighbourhood watch or arrest. You can see if there's violations of parole.

This is something that is happening in many places in the world as an alternative to detention systems are being used. In the United States, there are hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers in the US who are being tracked by devices that are similar to this. This is also what's being used to target Palestinians. In industry documents from these tech companies, we see a lot of discussion of how what they're building in Xinjiang shouldn’t stay in Xinjiang, that it should travel elsewhere. They talk about how the Belt and Road Initiative, which is China's international development initiative, contains 60% of the world's Muslim population, and so the security industry in Xinjiang presents a market opportunity that's with huge and unlimited potential.

The implication is that wherever there's Muslims, these kinds of tools should be used, because Muslims are inherently a threat, they're inherently extremists and inherently terrorists. And so having safe city systems that will track their movement or the ways in which they live is essential if you want to have a safe society. This is how the industry is presenting itself. This is what they want to do.

And we see that they are doing it. Meiya Pico, the data valence company that is trying to compete with the Israeli company Cellebrite, is now using the Belt and Road as a way of finding new markets for its tools. They're doing trainings all around the world, but particularly in the global south. These kinds of tools, which can be used to track people's digital behaviour and past digital life, are now being manufactured and sold at scale.

Hikvision is another company that is also beginning to market its things around the world. Around 25% of its sales are now related to exports. It's working in a hundred 90 countries. It's parent company CETC, which I mentioned earlier, is what builds the Integrated Joint Operations Platform in Xinjiang, which is the largest data assessment tool that is connected to all of the other surveillance systems. Hikvision was the second largest contractor to build the biometric surveillance safe city systems. It received USD275 milliion in contracts to build population assessment systems that had this color-coded stop-light system of green, yellow and red. These systems went from the mosques and transit centres and cities to the camps that are connected to those locations. Hikvision also developed tools to automate the detection of Uyghur faces, along with many other computer visioning companies in China.

To really narrow in on the comparison between Xinjiang and Israel, if we follow Hikvision sales, we see that Israel is now a primary market for the company. They have a Hikvision Israel website and they have another distributor, HVI, that is selling their tools to the Israeli military. There's 54,000 Hikvision camera networks in Israel as of 2021, and they're a primary service provider for the Israeli Red Wolf facial recognition system, which is the system used in Hebron, the West Bank, East Jerusalem to track movement through the infrastructure system through transportation and at checkpoints. These systems are meant to alert police and the military to potential incidents in real time, so they can be responded to before anything actually happens.

It can of course also just track people who are on the watchlist. And we see in the data that's being produced through the system, and through other research, that this system is also producing a stop-light system of green yellow and red. Red again being the untrustworthy category; Palestinians are in the red category should be immediately detained.

It's integrated with the Blue Wolf System, which is the mobile policing system interface that the Israeli police and military carry on their phones. Both of these systems are then integrated with the Wolfpack System, which is the data integration system. This is similar to the Integrated Joint Operations Platform in Xinjiang built by CETC.

What the Israeli military say about the Wolfpack System is that it makes Palestinians searchable in real time, it has automated capacities that looks at patterns and movement, it enables them to locate people anywhere, anytime, in the past and in the present and predict where they will be in the future using the system.

There's some great scholarship that you should be looking at if you want to know a little bit more about how these systems are used and their effects on Palestinians in their usage. A friend of mine, an anti-colonial Jewish American scholar named Sophia Goodfriend, is doing her research in Israel, can speak Hebrew and is Jewish, so all these generals and police people working in the intelligence units are actually happy to talk to her until they figure out that she's gonna critique what they're saying. She has really unprecedented access to the ways in which the military talk and think about the building of these systems. She also speaks Arabic and works with Arabic language, she's going also into Palestinian homes to ask them how the surveillance is changing their lives.

If you don't have time to read an academic article, there's also a really great short piece from Al Jazeera that interviews Sophia and talks through how the Wolfpack System works.

This is what it looks like in the video: it looks like automation assisted apartheid. You see children having their image captured. Sophia talks about how there are contests among different military units to capture the most images of people's faces and link them to their IDs. If you meet a certain quota or certain number, then the military will get a movie night or other kinds of rewards. In the film you see a discussion of like what this does to Palestinian families, how it really constrains or narrows the space that's available to them. Many people feel as though they shouldn't leave their homes because they'll be tracked immediately. And if they have a family member who's in detention, family member who's connected to Hamas or to other government organizations in any way, then they are on suspected watch list.

Another piece that Sophia has written recently is on how Israel's counterterrorism law has been expanded to focus on forms of speech. So consuming or possessing any materials that can be construed as supporting Palestine, supporting Palestinians, supporting the struggle in Gaza, or supporting people in Gaza, those things are now criminal content that could be prosecuted or potentially be prosecuted. This system is also affecting 1.5 million Israeli Palestinian citizens - Palestinians who live in Israel and have Israeli citizenship, chilling their speech, and making it impossible or much more difficult for them to be politically active.

The most troubling aspect of where technology is going in Israel, though, is in the way that dataveillance and the digital enclosure is being used to assist in the automation of assassination, which is basically how they produce targets in Gaza. We all know that there is the mass killing of civilians, but they are using automated systems to choose their targets, knowing that civilians will be killed, but having some justification in doing the killing because they are able to geolocate some member of Hamas, just low level workers in the Hamas government, or somehow connected to the militant wing of Hamas. This is a really important piece at +972 Magazine, and you should check it out if you want to know a little bit more.

In a general sense, what's happening in Israel and what’s happening in China is connected in the way that surveillance work and state security is becoming another form of tech work, how working in state security is part of building a career in technology as a technologist. In Israel, because of the military services is mandatory, people choose in high school to study technology to prove that they will be a good fit for the intelligence units. This is because they understand that once they get into the intelligence units, they'll be able to move very quickly from that to tech companies after the military. There's also this back and forth in terms of intelligence units being structured as tech companies, and tech companies contracting with intelligence.

The same is happening in China. Much of what was built in Xinjiang was built by private companies, but they work directly with the Public Security Bureau, and so there's this back and forth people moving between the private sector and the state security sector all the time. We see the same happening in the United States with Palantir and other companies working directly with the military. People who are in high income positions as they're being drafted into the military, are often those that end up working in these intelligence units in Israel. It's also a pathway for social and economic mobility in China.

Tech is a huge part of the of the Israeli economy and the Chinese economy. In Israel, 14% of all Israeli workers work in tech, so over 500,000 people. 48% of Israeli exports are technology related, most of it around cyber hacking, security systems, and digital forensics. It produces USD71 billion for the Israeli economy. In China, there's a planned approach to investment in artificial intelligence, this from the Xi administration, which is they will invest a USD150 billion in AI research by 2030. They hope that AI will bring USD7 trillion to China's GDP. When it comes to data valance or mass data analytics tools, a lot of this is focused around safe city systems and an attempt to compete with Israel and the United States.

There are a lot of other things being built by AI in China, and they're also the leader now when it comes to electric vehicles and other approaches to green energy and the environment. So I'm not trying to say that like all of China does is build surveillance. I'm just saying that it's also building the same things that Israel and the United States are building and trying to export them especially to global south countries where they often have tighter trade relations and also can sell them at a lower price point.

The point of what I'm talking through is that we should think about China, Israel, and United States at the same time and understand that all of these states are modernist states, which means that they are built around an imperial formation, that they centre around maintaining power for those that are already benefiting from the society. And so if we see China doing the same similar things to what we've seen in other colonial situations, we shouldn't be surprised. This is what modern states do. We need to be able to oppose these things simultaneously, and I think one of the ways to get at that is to show their linkages, how these things move in very specific ways, and understand what this means on the ground. It produces extreme brutality, which is a normalization and unthinking of violence. It justifies mass killing in Israel and mass internment in China. If we care about abolition, we should care about both of these cases at the same time. We should work to abolish the police and the prisons everywhere. And we should also be tuned in to emergencies in the world, where, as now in Gaza, atrocities are occurring.

Q&A

PSAN & Darren Byler (DB)

ZZ: Thank you so much, Darren, for a very, very informative talk and a very timely and important one. I do want to address one of the things that you said at the end of the presentation regarding the fact that a lot of contemporary movements don't usually bridge the two struggles together and for reasons that we know; there are plenty of binaries between say, democracy and authoritarianism, between socialism/communism and liberalism that movements usually organize around. And so these binaries really make it almost unimaginable to think about the fact that all modern nation states, as you said at the end, regardless of regime types, ideologies, or whether they're located in Global South or Global North, are settler colonial and imperialist in “mimicry” in your words as well. From this premise we can say both the Uyghur struggle and Palestinian histories of resistance start from when the first settlers set foot on the land.

And so my question is more broadly about the historiography of counter-insurgency and contemporary surveillance studies. As made extremely clear in the political discourse around Palestine here in the belly of the beast, we want to be really careful about how we start thinking about the history of all this. As we see in your talk, you know, counterterrorism and counterinsurgency are super interconnected and more often than not interchangeable. But as we observe in the critique of surveillance capitalism, you see contemporary academia and the NGO industrial complex, including Amnesty International, tend to focus solely on counterinsurgent techniques without first addressing insurgency against colonization and capitalist racism to begin with. I always question the fact that these discourses prioritize the discussion of anti-apartheid as kind of civil rights agenda (meaning equity and shared power with the colonizer) over the kind of anti-colonial resistance (meaning land back and the end of colonialism by all means possible). Which brings to my question: how do we contextualize this, you know, very informative and important research in the long history of resistance and what's the implications of surveillance studies for organizing anti-colonial insurgency? I know this is a difficult question, but a question that is very relevant to people who have been in the organizing scene and want to think about these questions as both academics and organizers.

DB: Those are good questions. In terms of the history of counterinsurgency, it really begins with the post-colonial movements of the 1950s-60s. Prior to this, there might have been discussions of guerrilla warfare or something like that, or they continued on at the same time. But with counterinsurgency, the French Algerian case, which you see in the film Battle of Algiers,is a primary example of how states and militaries start to think about the need to map populations, because you need to know where everyone is in order to figure out who's insurgent, who's in the either/or category – which is the majority of people, and those who are counterinsurgent – their collaborators among the colonized populations.

There are a lot number of tactics to get at this. One of them is mass detention and killing, assassination of people seen as in key positions of power. This happened in the Algerian case. And then there's also psychological warfare, telling everyone that the insurgents are terrorists as a way of delegitimizing their claims, not acknowledging the structures of violence that they are confronting and instead saying these people are irrational, they're backward, basically using all of the tropes of the colonizer: the reasons why we should colonize you is because you're heathen, you’re backward, your uncivilised, you’re barbarians, your brutes, all of those things. And so the category of the terrorists is the contemporary instantiation of older colonial tropes.

The global war on terror - at least among the western states - has moved that into a different space, re-legitimising colonial tropes. And military theory as it's been developed now is saying that counterinsurgency or counterterrorism is the only mode of military action that's available and so that's how we see what the scholar Madiha Tahir calls “distributed empire,” where the tactics and technologies of empire get taken up everywhere in the world by basically every state that has a military.

So how do you organize in opposition to these things? It's challenging. I mean, one of the things is because these things are happening digitally now, it means that they have a digital life that can be detected in almost real time. And so I could get these materials from The Intercept, and within the space of several months, begin to show what was happening. So there's exposure that can happen and you see the same happening in Israel now, with the reports I was talking about. Those are actually coming from the inside of the machine. They are intelligence officers who are drafted into those positions who maybe initially didn't know what kind of work they were doing or maybe supported the work because they were inculcated in a Zionist ideology, but became disillusioned with it. So even the reporter Yuval Abraham, who did the exposé on the mass assassination factory and about how AI is being used in targeting in Gaza, is a former intelligence officer who has turned on his intelligence unit and is actually getting intelligence folks within the unit to speak to him.

And so I guess that's one fracture in the system, where you can work with technologists who actually built the basic science of these things, get them to expose their own work, and also begin to push for some change to design tools for liberation rather than for harm. But of course there's a structure of incentive that prevents this from happening. It’s really hard to get technologists to care. They will say, instead of, this is a political problem, it's not their problem. They're just building the tech and how people use it is up to them. So both technologists we have interviewed in China and in the US would say, in the most normative of responses, “it's not our fault.” But there is people that understand that it is their fault and that they have power because they're designing these systems. And so I think Tech Won't Build It is a one kind of response.

But in terms of how you can help people that are on the ground in Gaza, how you can help people in Palestine and in the Occupied Territories of Palestine, or in Northwest China, that is a much more difficult thing to ask. A lot of it is supporting where we can, the people that are in diaspora, and acknowledging the struggle that they're confronting. I’m a settler scholar from Ohio. I'm not Uyghur; it's not for me to decide what the future for Uyghurs would look like. I need to turn on the microphone for them. And so I tried to do that. I think, though, as activists we also have a role to play. It's not as though we should stop thinking about what kind of world we want. I think we can maintain our friendships with people who are most targeted by these systems and try to push for the political and economic systems that we want or the values that will build the world we want. So I think we have a role to play even as we are allies or accomplices in struggle.

Gin: How do we dispel claims that the Uyghur genocide is mere CIA propaganda from within the pro-Palestine movement, and how can we create constructive conversation for people to learn about what is actually happening in that area? How can people build solidarity with the Uyghur community without falling into the US right wing anti-China agenda? And how do you see the prospect of building solidarity between Palestine and East Turkestan, given their respective support from the US and China? As scholars and activists, what are our roles to build solidarity and how do you find balance between doing the needed critique of the Chinese state and addressing rising xenophobia?

DB: I think some of the polarization of campism that we see in the world is a result of some ignorance, of not actually knowing the thing that we are positioning ourselves against or for. But there is also a real concern, which I also have, about reproducing US talking points and feeding forms of anti-Asian, anti-Chinese racism. Those are concerns that all of us should have. So I think in terms of how do we build forms of solidarity between Palestinians and Uyghurs, listen to what Uyghurs say, which is also not easy because Uyghurs are being silenced actively and those who have a platform are not necessarily representative of Uyghurs.

I'll just give you a few examples. When I was living in the Uyghur region, one of the first questions people would ask me when I was meeting them for the first time is: what do you think about Palestine and Israel? They were testing me to see where my political loyalties lay, and how I identified myself with colonial regimes versus with people that were being actively colonized. They were also testing to see whether I was Islamophobic or not. But they also genuinely cared about Palestine. They were thinking about them often and also about people in Kashmir. They saw themselves in very similar positions.

I published something a week or two ago about a Khazakh molla (a religious scholar and cleric). And the most damning reason that the police found for why he should be given a 17-year prison sentence was because he possessed a book that professed to the liberation of Israel and Jerusalem. It was a pro-Palestinian book. And so they said, because you have this book, we know for sure that you're a terrorist, which is just crazy because from the Chinese state perspective, they are now saying that they support Palestinians. But I think we have to understand that they see it as more of a proxy war with the United States, and we can see with facts on the ground, where they are investing their money, that in actual fact they don't necessarily care about Palestinian lives.

So I think we just have to take a non-statist approach to understanding the world and understanding the future we want. We have to simultaneously critique the US and China. I tried to do this in my work as much as I can, which means that I get disinvited from certain spaces, especially right wing spaces because they realize that I'm going to critique them while I'm also going to critique China. So I think being able to do both simultaneously is the task at hand. I'm thinking back to a comment from Cornel West kind of along these lines. Cornel said that, to do this work, we have to improvise. It's like jazz. That’s just one of his favourite metaphors. We need to be able to side on the side of the oppressed in every moment. And that means not supporting a state that we see as a wedge or a political rival to another state that we oppose simply because of that. We need to think about the communities that are most vulnerable, who are the most targeted, within all of these states, and be on their side. And think from their positions. That's not an easy thing to do.

P: I have a question related to sanctions, sanctions as in BDS, but also as in US government sanctions. As we all know, the US federal government has been imposing various sanctions on Hikvision and Dahua for over five years. US federal agencies are prevented from buying Hikvision technology, and US persons are barred from investing in Hikvision, and also more recently, Hikvision subsidiaries are prohibited from buying parts from the US. The concern, real or otherwise, about the so-called national security is the recurring rationale behind it (we also see this in the recent TikTok ban). But the ways in which Hikvision is used against Uyghurs and other Muslims in China is also another issue they factor in. This is of course also because of the efforts from the Uyghur advocacy NGOs. But, meanwhile, we are seeing how US hypocrisy has never been clearer in this genocide against Palestinians. This makes people question if the US government and the right politicians are just weaponising Uyghur human rights issues for their own anti-China agenda. So I'm wondering, what is your view on the US sanctions on Hikvision and is it really helping Uyghurs or having that as its goal. I think this is an important question to think about around BDS, because other than the grassroots boycott campaigns, government-level boycott is also one of the key strategies to check apartheid Israel. In the past few months we have seen Malaysia banned Israeli ships from docking in Malaysia as a form of sanctions, as well as arms embargo in Colombia and the sea blockade by Yemeni Houthis. Do you think, on the issue of oppressive technologies, more countries should join the US to take similar moves in sanctioning Hikvision, or how could they sanction, or take action, differently to genuinely extend solidarity with both Palestinian and Uyghur people?

DB: The hypocrisy is so stark when you look at these two sites. In general, in my work I try to expand the object of critique to point out that surveillance is not a Chinese problem alone, it's a US problem. Much of the technology used in China finds its source in the United States. It's been adapted to new purposes, in a different political environment, but it's more or less the same technology. So we need to oppose that technology. There's no reason we need biometric surveillance tools. They extend the power of the police, which we know is violence work, nd the police order itself is anti-democratic. It's anti the people. So we need to oppose policing. We need to oppose the technology and its use in policing everywhere, simultaneously. So we should boycott the United States. We should boycott China and we should boycott Israel. That's like ultimately how things should be.

I think we should use all the tools we can. One example that you can turn to is the boycott of South Africa, which had a dramatic effect in terms of ending apartheid there. But of course, it is a capitalist boycott in a lot of ways of South Africa. So it wasn't a transformational approach. It wasn't a revolutionary approach. It was, you know, we're going to oppose this one while we keep other wars going at the same time.

So it's a global problem, which means it needs a global solution and global solutions are really, really hard to even imagine. But that's what we need. We need global grassroots movements and then we need regulation that meets those movements in some ways. But getting there is really hard. It's an open question. I don't actually have good solutions to address it. I think it's similar to how we're thinking about climate change and how we address that. It's a global problem. We need everyone on board. And there are some states that are doing better than others in addressing it. And so I think we can learn from each other. I said earlier that all modern states are colonial or imperial states and that is true, but they're not all equally the same in terms of the horrors that they produce. Colonization, imperialism, and anti-imperialism and decolonization are dynamic things. Some states have truth and reconciliation commissions that are somewhat surface level - I'm speaking from Canada. But because we have it, I can actually do decolonial work. I can talk about it in the classroom. I can push students in that direction. And so, having a mandate from the state is useful. Some regulations are useful.

I think how [Hikvision] being used in the US is really around a new tech Cold War. It's part of the US war machine wanting more investment in opposition to this imagined China threat. Unfortunately, that's a lot of how the Uighurs are being used in that regard.

I think it's useful, though, to not support Hikvision in any in any capacity. And so in that sense, I'm on board with, a boycott or a sanction of it.

Questions from audience

Q: What do you see as the legacy of the 1960-70s anti-colonial and internationalist solidarity between the third world countries like China and Tanzania and those oppressed in the US? There seems to be a romanticization of this movement and of Chinese radicalism during the Mao period in fields like China Studies and Asian-American Studies that stifles discussions of contemporary and historical Chinese oppression of ethnic minorities.

DB: So the third worldist approach, I think, is a really important moment and something we're thinking about as a way of building international solidarity now.

I think China's role within it was important, but it was mostly a space of refuge or kind of a third space. It was less central, in some ways, to the role that was played by activists in places like Indonesia or Malaysia or Egypt.

One of the things that came out of that movement was, especially when you're thinking from Indonesia, thinking about infrastructure and shipping because that was how colonialism arrived for them. So colonizers are thinking “that's what we should target.” So the Suez Canal was a point that they were focused on. It's like we need to stop the sinews of global capital: the logistic system. You see the same thing happening now with what the Houthis in Yemen are doing. They’re using the weapons and tools that are available to them to take a stand against their own historical experience of oppression; the Saudis were bombing them with US weapons as well. And so they're taking a position. I'm not necessarily advocating for it, but I think about maybe worker strikes at the docks as a way of building on the third worldist movement because that's the sort of thing they were thinking about. There is often some romanticization when it comes to thinking about Maoist China because if you talk to people that were there at the time, there were some folks that benefitted from it and felt as though there was political progress being made, but there was a tremendous amount of suffering as well. There was a lot of factionalism, of oppressive forms of power that are being weaponized in that moment in China. While it provided forms of support for third worldist elsewhere, I think it was also instrumentalist in how it did at times. There's a lot more we could say, I think I'll just stop there.

Q: I’m interested in learning more about how the normalized checkpoints that segregate Han and Uyghur people also exist outside of the prison complex in Xinjiang and were also applied to other parts of mainland China during COVID. We have also seen a rise of normalized surveillance around the world here in Canada as well as in the US. There people who are in our IG comments section saying, “what's wrong with CCTV? Why isn't that making us safe?” What do you think about this question?

DB: I think the person asking the question is absolutely right that these systems are now being normalized. Public health surveillance around COVID has a certain logic to it. There were fairly good reasons why you would want to prevent the spread of the pandemic and so on. But what we saw in happening in China is it's being used by local authorities in quite arbitrary and really oppressive ways, in ways that responded to the black box of their assessment tools like their phones, giving them a certain code, and then they would enact a response based on that code without actually necessarily looking at the science that was behind it. People saw those systems used in really disempowering ways, where they felt like they lost control of their own lives and of their families. There was a lot of violence.

And I think some of that capacity now continues on in China, because once the tools are there and they're all integrated, it's not as though they go away after the state decides that they're no longer going to attempt to control the pandemic. They can be used for political purposes. Many technologies are dual-use or multi-use, but I think surveillance technology is particularly dangerous because it's in the word itself is the is the framing of oversight. The overseer emerges out of a slave economy in the plantation economy in the US. It's about distribution of power.

People want to have forms of safety, and I think that's something that is a value that we should want. But safety is different than security. Safety is something that comes from the community, that responds to community needs, that is addressing underlying issues within the community, like housing and basic needs, education, and jobs. Those are the things that need to be addressed, not the treatment of the symptoms of security. This is what security does, it establishes a police order, which means that it maintains the social order. So those that are excluded remain excluded. Those that are benefiting will continue to benefit. And so it reproduces forms of inequality.

I think we need to be really careful with the term “security”, also with the term “terrorism”, and think about what does it look like from the people that are excluded. Security for whom? Who is being made insecure by this security? And even during COVID, we saw this happening to migrant workers; insecurity being produced by the COVID restrictions happening to those are differently abled, to the elderly. And so I think from those positions they help us think about what kind of technology use we want in a society.

Q: You spoke about the global export of this technology. Are the customers primarily state actors? Do you have any insight on increase of this technology in Europe? Another person asked whether we should extend this to India where they witnessed political violence against the Muslim minority, specifically Kashmir?

DB: Mostly these are being sold to police units, and also to government units. The safe city systems are systems that are usually operationalized at the level of like an urban centre or metropolitan area. They are sometimes quite large, and can include millions and millions of people. They are framed as part of a smart city system, which is about traffic management and waste management and you know the basic infrastructure of the city, Something that the philosopher Michel Foucault would talk about as security which is about the circulation of the things that you want and the lowering the rates of circulation of things that you don't want.

So often it's states and cities that buy these things. They buy them because they believe in security, but also they believe in ideas of progress that have been inculcated in them through rhetoric around modernization. To have a global city and to have a cutting-edge city, you have to have a safer or smart city. And so, there is this idea of progress and citizen support for that. So there is buy-in from regular folks as well, people that want security and new technology. And I'm on the side of technology also, I like to use Wi-Fi. I like to have access to the world of knowledge and to be able to circulate knowledge. It's just always the question of who benefits from these systems, who are excluded by them? What safe cities do in general is they exclude undocumented people and people that are racialized. They push them into ghettoized spaces, into the grey economy where they avoid surveillance. And so it shapes the life path of those that are targeted by these systems or, banished by them, while at same time provides us with this idea of feeling of security as protected citizens. So we should understand that our trade-off is that, that people's lives are being directly affected by our imagined sense of fear as protected people.

In general, these systems are systems that need to be rethought, and we need to think about them in a global level.

Closing Remarks: Call for Action

There were a lot of questions that didn't get answered and we encourage we all to continue reading Darren's work and to learn about the historical and the current contexts on the topic of state surveillance by China and Israel. Palestine Solidarity Action Network would like to urge the community to centre the voices of the oppressed: The Uyghur community, Palestinians, and also the most vulnerable in whichever country that you're in, and really finding power in, whether you're in academia, whether you're in corporate, all sorts of different networks, finding the people within. And that's the community, that we take care of each other rather than clinging onto the state and thinking that the enemy of our enemy is quite our ally, which is not the case.

In the end, we want to direct attention to the Hikvision campaign that PSAN has spearheaded. Sign the petition, find your local Hikvision office, plug into local organizing, and protest in all the ways you can do so.

And so, it's a call to action to the community that we'd like to end on.

Share this post